Below is the short – 20 minute long – talk I gave at the Radical Histories / Histories of Radicalism conference at the beginning of July. I was presenting alongside Sarah Wise, speaking on the radical venue Eclectic Hall on Denmark Street, and Judith Walkowitz, who discussed the debates and demonstrations around prostitution in King’s Cross in the 1980s. (Abstract.)

Although the strand was ‘Radical Londons’, none of the three papers took London as a whole, but concentrated on small parts of it, at different times across three hundred years. My contribution focused on one section – weavers – of the population of the debtors’ sanctuary of Southwark Mint. The paper is more or less what I delivered, minus a little ad libbing: I couldn’t resist singing the song the Minters made the bailiffs they pumped sing:

“I am a rogue, and a rogue in grain, And damn me if I ever come into the Mint again.”

A recording was made, though not yet released, so you will be able to hear my dulcet tones at some point in the future.

In the discussion afterwards, a couple of things came up. Firstly, writers in the Mint and the other sanctuaries. There were a few, such as Tom Brown who took to Baldwin’s Gardens a few times, and Nahum Tate, poet laureate, who died in the Mint in 1715. It’s a source of frustration that none wrote anything substantial about the sanctuaries

As is the way with these things, I also got asked a couple of questions I couldn’t answer. One was to do with the administrations of London, and how various areas had particular and peculiar rights. Quite simply, organizationally London was quite chaotic; it was subdivided into (secular) wards, covered by a (religious) parish system as well, stimuated urbanization outside its own control and bounded by counties that did not have the capabilities to deal with that growth. At the same time, there was an order of sorts: no sanctuaries within the old city walls, and the powers of the City of London. Beyond depicting the chaos of it all, I couldn’t really describe or comprehend it.

Another question related to the usage of the word ‘Republic[k]’. I think I have presumed two things in the talk below: that the word would have echoes of the Interregnum and therefore express an active, radical, anti-monarchical aspect, and that it is fundamentally geographical, refering to an particular area.

My feeling now is that neither is true. The word may well have been more commonplace and not always have such ardent political connotations. Furthermore, as in the idea of a ‘Republic of Letters’, it need not imply a particular space but can refer to a dispersed community. As such, the term also moves the stress from place to people. This is something I need to consider more carefully.

I was also asked about Huguenot names appearing on the Minters’ lists. I need to check this carefully, but my impression is that there are very few French-derived names.

This Little Republick: The Weavers in Southwark Mint

Introduction

Good afternoon. My name is John Levin, I’m a PhD student at the University of Sussex, writing a thesis on imprisonment for debt and debtors’ sanctuaries in London in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Today I’m going to talk about Southwark Mint, the longest lasting of these sanctuaries, the weavers amongst its population of debtors, and the politics of the Mint.

Sanctuaries

A debtors sanctuary was a place where there was some claim of exemption from arrest under civil process. Although there was a long tradition of religious sanctuary, of inviolable church territories where even criminals could take refuge, by the time of the restoration these exemptions were for civil matters only, and therefore fundamentally for debtors as they could be prosecuted and imprisoned for nonpayment of debts. After the reformation, these rights were never clearly settled nor abolished, needing to be asserted and enforced amidst a number of contradictory statutes.

At some time in the 1670s, – 1673 is the earliest date I’ve found of debtors, in the savoy, asserting these rights – communities of debtors were formed in certain presumed ‘privileged places’ in London, where they asserted their immunity from arrest by bailiffs. If you look at this map – from a project I’m working on with Nick Valvo of Northwestern University, called Spaces of Exception . org – you’ll see a cluster of markers on the north bank of the Thames. The markers note the places in London named in the act of 1697 that abolished the sanctuaries. These, centred round Whitefriars, constituted ‘Alsatia’, so nicknamed by the journalist Henry Care in 1676, and the most renowned of these refuges. The term alsatia is still used today to denote a place outside the law, but it is important to remember that whatever cover it provided for criminal activity, the core population were civil debtors and the legal exceptions were of civil law.

All the sanctuaries were outside the City of London’s walls, with only Whitefriars and its neighbours in the City at all, in the ward of Farringdon Without. [Blackfriars and St Martin’s Le Grand were not debtors sanctuaries at this time.] To the East, the Minories, once an abbey and in 1697 part of the Liberties of the tower of London. To the North, Baldwin’s Gardens, Holborn / Middlesex, possibly having some inherited religious rights. Transpontine, there were three sanctuaries, Montague Close around Southwark Cathedral, the Clink and the Mint.

Although some of these sanctuaries had some sort of religious precedent – Whitefriars was as the name suggests a monastery – others did not. Places like the Savoy, the western-most point on the map, were, as part of the Duchy of Lancaster, independent of the local administrations. Similarly, the one sanctuary that revived after 1697: Southwark Mint, the bottomost marker on the map. The Mint had no religious precedent – as its name suggests, it housed a mint and as such was directly under the control of the king. When part of Southwark – Bridge Ward Without – was sold to the City of London in 1550, the Mint was expressly excluded from the area purchased. Even though the Mint ceased operation in 1551, and over the next century tenements were built there, the area remained, and retained the status of, a Royal Palace.

Despite suppression by statute, the Mint revived in the early 1700s, due to a combination of unforeseen legislative side effects, of bankruptcy and debtor prisoner relief acts, of having another spatial claim by being entirely within the rules of the Kings Bench prison, and – most importantly – debtors willing to physically defend themselves against the bailiffs.

When Southwark Mint was abolished in 1722, an amnesty was offered for the relief of the debtors residing there, similar to the regular relief acts for those in prison for debt. Those with debts of under £50, on giving up their property, would have their debts written off. Because of these measures, requiring the minters to give notice of their application, we have, at its end, a veritable census of Southwark Mint, giving the names, occupations, place of last residence, and from which gender can be divined.

This practice, of publishing details in the London Gazette, was first established by the act for the relief of imprisoned debtors in 1712. Similar acts were passed in 1720, 1725 and 1729, and I shall be drawing upon those lists as well.

A note on numbers: whilst this sounds like a clean and clear source, these lists are not. There isn’t a standard orthography, there’s curious spellings, strange geographies and so on. Also, the lists have doubles – not many, but the problem is in identifying them rather than their number. Consequently, the figures I will be giving, whilst I think them broadly accurate, and not precise.

Weavers as debtors

The Mint relief lists published in the London Gazette total 6,256 entries. Of these around 600, some 10%, gave their trade as weaving, the largest single occupation. The majority came from London, although there were contigents from Norwich (around 30) and Dublin (around 20). And within London the majority came from the East End, from around Spittlefields, Whitechapel, Shoreditch and Stepney, with a sizeable minority coming from south of the River, Southwark and Bermondsey. As with the sanctuaries, they came from outside the walls of the city of London.

By contrast, a mere 48 male weavers were among the debtors applying for release under the 1720 act, and of them only 9 were from the London area. After the abolition of the Mint, of 66 weavers applying for release in 1725, half came from London. But by 1729, 148 weavers were in prison for debt. (A further 29 surrendered themselves as fugitives, under the terms of the act.) This mirrored the increase in absolute numbers of people imprisoned for debt (and applying for relief): from less than 2 and a half thousand in 1720 to over 4 thousand in 1725 and 6 thousand in 1729. An illustration both of how successful the Mint was, and how much it was needed.

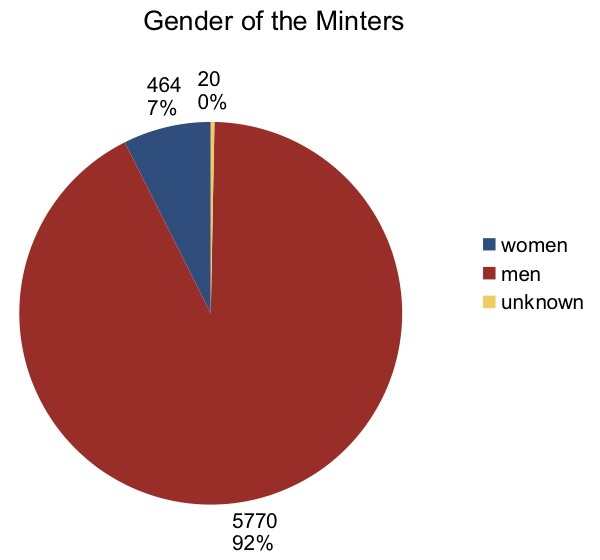

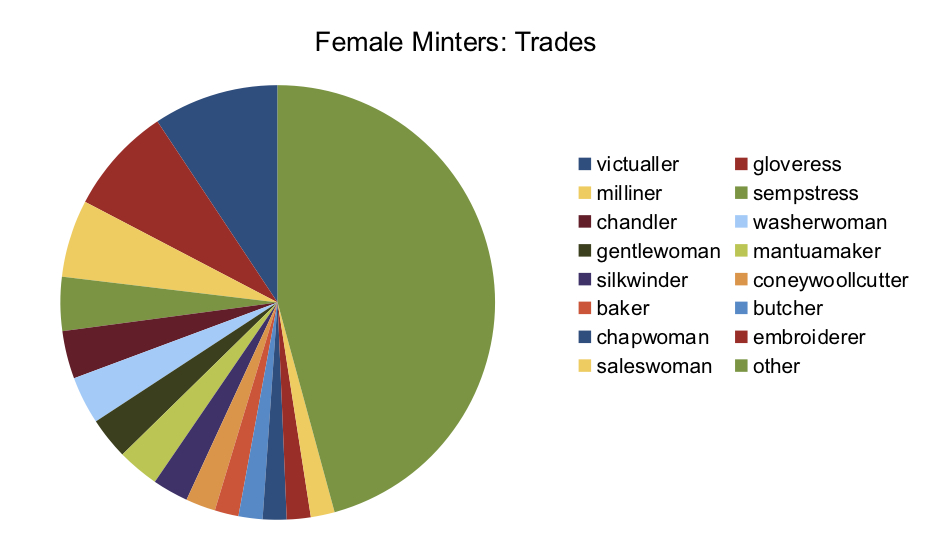

The weavers counted thus are overwhelmingly male. Women made up about 7.5% of the names on the Mint relief lists, totalling around 450 entries. Over 90% of the female minters came from the greater London area (London, Middx, Surrey; only 42 from elsewhere). Women generally comprise between 8% and 10% of the prisoner relief lists. How many women were weavers is unknown: the entries in the lists often give a woman’s marital status rather than occupation, and due to the doctrine of feme covert, whereby a wife’s debts were – along with her person and property – subsumed into her husbands’, the vast majority of these statuses are either widow or spinster. The absence of servants also adds to the general gender imbalance; I have yet to calculate the proportion of female debtors as a proportion of the general adult unmarried female population

There were many other trades represented in the Mint, the largest being bricklayers, tailors, butchers, bakers and candlestick makers. There were many in retail, traders and victuallers, around 200 farmers and husbandmen, less than 100 labourers. And some were not plebian, but gentlemen (130) and even 11 brokers, perhaps suffering from the South Sea Bubble. But the weavers were the largest single group, followed by others in the clothing industry.

Why were weavers in debt? On this the relief lists are silent. We don’t know who their creditors were, nor how much they owed. The 1723 act set a maximum of £50 of debt to be eligible for relief, so we do know that the debts were not individually enormous, although widespread. But other than that, without the specific stories, we have to rely on larger, macro-economic conditions as an explanation.

Weavers’ wages could be low and, on piecework, irregularly paid. Overheads like renting a frame require a continual flow of work, which couldn’t be guaranteed. In terms of economic structure, a lack of circulating coin made the use of credit inevitable, and meant that one could be nominally solvent – owed more than owing oneself – yet still threatened with imprisonment. Cycles of war and dearth, and foreign competition also made the weavers lot precarious. And the whole period of the so-called ‘Financial Revolution’ was punctuated by economic crises, from the stop of the exchequer, via the great recoinage to the south sea bubble.

Thus far, the weavers in the Mint. We turn now to the weavers considered as *of* the mint, as active contributors to the Mint.

A Little Republick?

“Of all the groups of workers who used such devices to coerce their employers, none had so long a history of struggle, none were so remarkably persistent, and, maybe, none so violent as the silk weavers of Spitalfields, Moorfields, Stepney, and Bethnal Green.” Says Rudé, in his “The Crowd in History.”

Throughout the period of the sanctuaries, from the 1670s to the 1720s, the weavers were continually protesting, not just in London but throughout the country, wherever their trade had taken root. Protesting took two tracks: physical demonstration, in the streets, and arguing ‘in the public sphere’: petitioning and campaigning for laws to set wages and to ban imports of calicos.

This dual strategy, of violence and negotiation mirrors the campaigns against imprisonment for debt. There, there was both physical action, fighting bailiffs and rescuing debtors from their clutches on the streets as well as rioting within the prisons, and public debate by means of petitions for amnesty and relief, and pamphlets as to the legal and moral rights and wrongs of imprisonment.

Beyond being present in the Mint, weavers were clearly active within it. At least one, probably two, of the leading Minters named in the Parliamentary inquiry of 1722 are found on the relief lists described as weavers. Weavers assembled in the Mint during the Calico riots of 1719; two arrests were made, both of weavers from Spittlefields. But the Mint had, aside from the rioting and petitioning, an extra dimension, of organizing governance over a territory.

The pamphlet “Memoirs of the Mint”, of 1713:

“the [species of government is] Democracy, and extends its Jurisdiction throughout that part of the Country known by the Name of the <i>Mint</i>, which Government is excercis’d by a <i>Triumvirate</i>, call’d Stewards; who sit to despatch Affairs of State, at three Principal Offices, which are so many Entrances to their Dominions. Each of these is attended by six Representatives of the People, who bear the Character of <i>Beadles<i>, with their Subaltern Officers, under the Appellation of <i>Spirits<i>; these execute the Commands of their Rulers.”

A democracy, with representatives of the people! Or in even more radical terms, three years later, Thomas Baston, print maker and sailor, wrote whilst imprisoned for debt in the King’s Bench:

“There is a Place on the other Side of the Water, in St. George‘s Parish, call’d the Mint, where a great Number of unfortunate Persons have agreed together to recover a little of ancient Liberty, and rather to loose their Lives than be carry’d to Prison for Debt, tho’ they do not in the least resist the Execution of the law in any other particular; for this little *Republick* (in this respect) has a very regular Government, executed by their Senators, which they call Clubs, in which some Days every Week they meet together, and examine all Enormities, for they give shelter, or Protection unto none, except purely to the Unfortunate in the case of Debt.”

That there was a parallel government in place was testified to by the former M.P. for Southwark, John Lade, who had dispersed the weavers in the Mint during the calico riots: “that several persons within the Mint have set up a jurisdiction of their own; and take upon them to regulate and determine matters.”

At this point I’d like to make a jump, and suggest that the weavers, with their long and concerted political experience, wrought an organizational change in sanctuary practice. These words, democracy, republic, jurisdiction, were never used to describe the earlier debtor sanctuaries of the late seventeenth century. Nothing like it appears in, for example, Shadwell’s Squire of Alsatia of 1688. And clubs are found amongst the early proto-unionism of weavers, and of tailors, around 230 of whom are on the Mint relief lists.

This is rather speculative, in that there is very little evidence of this early trade unionism, due to a necessary secrecy. The other absence is writing of the Minters themselves, of whom we have only a handful of formulaic petitions and anonymous threatening letters, both of which were written for a purpose other than to describe their ideas. Whilst Baston cannot be dismissed out of hand, there is an air of rhetoric about his claims. It should not be forgotten that the Mint was also the site of the most appalling poverty, and continued to be so right up to the late nineteenth century.

What do we have aside from a small body of literature? The relief lists, which offer different methodologies for understanding sanctuaries, and for considering those debtors as part of a larger population. By analysing the composition of the sanctuary, and extrapolating from the individuals to their working communities, we can, if not declare outright for a republic, see the Mint as part of that plebian world, and not as outside of it as it was outside civil law.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Nick Valvo for making the map, taken and lightly edited from Spaces of Exception. Thanks to my fellow panelists Sarah Wise and Judith Walkowitz, our chair Carlos Galviz, and to the organizers of the conference.

This paper is released under the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike international license, 4.0.