When was the word ‘Alsatia’ first applied to Whitefriars? Cunningham’s Handbook of London (1850) states:

“ALSATIA. A cant name given before 1623 to the precinct of Whitefriars, then and long after a notorious place of refuge and retirement for persons wishing to avoid bailiffs and creditors. The earliest use of the name is contained in a quarto tract by Thomas Powel, printed in 1623, and called “Wheresoever you see mee, trust unto Yourselfe, or the Mysterie of Lending and Borrowing.” The second in point of time is in Otway’s play of The Soldier’s Fortune, (4to, 1681), and the third in Shadwell’s celebrated Squire of Alsatia (4to, 1688) ….”

Today, due to mass digitization, accurate searching, and hopefully accurate transcription as well, we can say that the first use in print was in 1676 – August 29th, according to the license declared on the cover – in a satirical tract ‘The Character of an Honest Lawyer‘, signed by one ‘H.C.’ According to this, such a paradigm of rectitude never

maintains any correspondence with the Knights of Alsatia, or Ram-ally-Vouchers ….

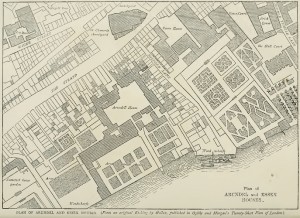

A brief mention, coupled with ‘Knight’ rather than the squire more common later, and with ‘Ram Alley vouchers.’ Ram Alley was a sanctuary in the precincts of the Temple, abolished along with Alsatia by the act of 1697; a ‘voucher’ was a witness-for-hire.

Before continuing with the chronology of the term, it’s worth considering where and when it wasn’t used. Powell’s 1623 guide to London’s sanctuaries, contrary to Cunningham, did not use it, and Whitefriars is mentioned only obliquely. Similarly, Brome’s play A Mad Couple Well-Match’d, dating from before the civil war but first published in 1653, has the lines:

I need no more insconsing now in Ram-alley,

nor the Sanctuary of White-fryers , the Forts of Fullers-rents,

and Milford-lane, whose walls are dayly batter’d

with the curses of bawling creditors. My debts are payd;

and here’s a stock remayning of Gold, pure Gold harke

how sweetly it chincks.

There’s a clear opportunity to use the term Alsatia here, especially given the explicit mention of Whitefriars. That it is not used implies that it hadn’t yet been coined. Furthermore, its absence implies that Whitefriars hadn’t become the epitome of sanctuary. From the literary evidence, that was not to come until the 1670s, after the Civil War, Plague and Great Fire of London.

The next use of Alsatia in its sense of refuge is a few months after ‘H.C.’, in the prologue to Settle’s play Pastor Fido, licensed December 26th 1676. Although used in passing, it is the first appearance of the squire:

Another keeps a Miss the modish way;

And when poor Duns, quite weary, will not stay,

The hopeless Squire’s into Alsatia driven;

Yet pretty Charming Sinner is forgiven.

Around this time, there’s a crop of passing mentions. Aphra Behn – once a debtor herself – refers to ‘New Alsatia’ in The Debauchee (1677), her adaptation of Brome’s play. Rawlins has a character as ‘foul mouth’d as a decayed sinner in the lower Alsatia’ (Tunbridge Wells, 1678); Otway’s The Cheats of Scapin (1677) and L’Estrange’s Citt and Bumpkin (1680) also make brief use of it.

It’s not until Otway’s The Soldiers Fortune (1681) that Alsatia and its denizens move out from the wings, with the squire’s portrait being fleshed out:

‘Tis a fine equipage I am like to be reduced

to ; I shall be ere long as greasy as an Alsatian bully ;

this flopping hat, pinned up on one side, with a sandy,

weather-beaten peruke, dirty linen, and, to complete

the figure, a long scandalous iron sword jarring at my

heels

Then in 1686 Alsatia becomes one of the settings of Aphra Behn’s The Lucky Chance. Bredwel describes the garrett of the debt-ridden aristocrat Gayman, who has sought refuge in Whitefriars:

I was sent up a Ladder rather than a pair of Stairs; at last I scal’d the top, and enter’d the inchanted Castle; there did I find him, spite of the noise below, drowning his Cares in Sleep.

….‘Tis a pretty convenient Tub, Madam. He may lie a long in’t, upright, there’s just room for an old join’d Stool besides the Bed, which one cannot call a Cabin, about the largeness of a Pantry Bin, or a Usurer’s Trunk; there had been Dornex Curtains to’t in the days of Yore; but they were now annihilated, and nothing left to save his Eyes from the Light, but my Landlady’s Blue Apron, ty’d by the strings before the Window, in which stood a broken six-penny Looking-Glass, that shew’d as many Faces as the Scene in Henry the Eighth, which could but just stand and then the Comb-Case fill’d it.

Two years later, Shadwell’s The Squire of Alsatia (1688), containing the first glossary to collect the term, made the fullest use of both the place and its Dramatis Personae. But by bringing the sanctuaries to the authorities’ attention, and inveighing strongly against such areas, it may have paved the way to the legislation of 1697 that stripped most of them of the right of refuge. It may therefore have a better claim to be one of the last, not first uses, of the term Alsatia.

Addendum: I’ve just discovered the Historical Thesaurus of English, which erroneously dates Alsatia to 1688. More interestingly, it also cites the personification ‘Alsatian’ to 1691, and places ‘Minter’, after the inhabitants of Southwark Mint, to circa 1700 – 1723.